We’ve Been Measuring Quality of Hire All Wrong

From Prediction to Pattern: A Cynefin Approach to Quality of Hire

Last week, I discussed the various ways we currently try to measure quality of hire and why they are all flawed.

The problem with our current methods is that we’re treating QofH as a complicated problem that, if we were only clever enough, could be measured accurately. But QOH is not a straightforward problem. It is not a complicated problem, but a complex one, and that makes all the difference.

A New Way to Look at QoH

Dave Snowden’s Cynefin framework is a helpful way to look at this. He divides problems into three categories. Clear (or Simple), Complicated, Complex, or Chaotic. Each is measured and treated in a way that maximizes effectiveness. Using his definitions and explanations, we can see that measuring the quality of hire is not a Clear or a complicated problem, but a Complex one.

Understanding the Distinction

In the Cynefin framework, complicated problems are like assembling an airplane. You can disassemble it, organize its components, and reassemble it. You understand the relationship between cause and effect in advance. The approach is straightforward: sense the situation, analyze it using expertise and best practices, then respond accordingly. Complicated problems have solutions that experts can determine, even if those solutions aren’t immediately evident to everyone.

Complex problems operate differently. In complex situations, you can only understand the relationship between cause and effect in hindsight. There are no predetermined correct answers. Informative patterns can emerge if you conduct experiments that are safe to fail, but even then, prediction remains elusive.

The distinction becomes crucial when we consider what hiring actually involves. Complex systems like markets, ecosystems, and corporate cultures cannot be taken apart to see how they work because your very actions change the situation in unpredictable ways.

Hiring puts humans into adaptive social systems where behaviors emerge from countless interactions among people, culture, circumstances, and timing. It is impossible to predict how someone will react when placed in a dynamic work situation.

Yet we try to approach quality of hire by assuming it is complicated. The faulty logic runs as follows: if we identify the right variables, create the right formula, and measure the right indicators, we can predict and control hiring outcomes.

Organizations invest heavily in performance ratings, retention metrics, time to productivity measures, and hiring manager satisfaction scores, attempting to reduce hiring success to their component parts. This is the fundamental category error. We’re applying complicated domain thinking to a complex domain problem.

How to Measure Complex Problems

This is a brief outline of a possible approach to identifying the variables that actually impact QoH.

Assume that Quality of Hire emerges from many interacting variables:

Recruiter assessment accuracy

Hiring manager judgment

Candidate motivation and cultural alignment

Onboarding and team integration

The company’s success or lack of success in the market

Because outcomes (performance, retention, and promotability) are context-dependent and time-lagged, QoH aligns with the Cynefin complex domain. Cause and effect are only apparent in hindsight, so the right approach is probe–sense–respond, in which you conduct experiments that are safe to fail, find emerging patterns, and respond accordingly.

Rather than attempting prediction, measurement in complex systems focuses on pattern detection. You must define the system’s boundaries, elements, and interactions, analyze the patterns, rules, and mechanisms that generate emergent properties or behaviors, and evaluate the feedbacks and self-organization that sustain them. You’re looking for emerging patterns retrospectively, not trying to establish predictive formulas that work prospectively.

A Practical Approach

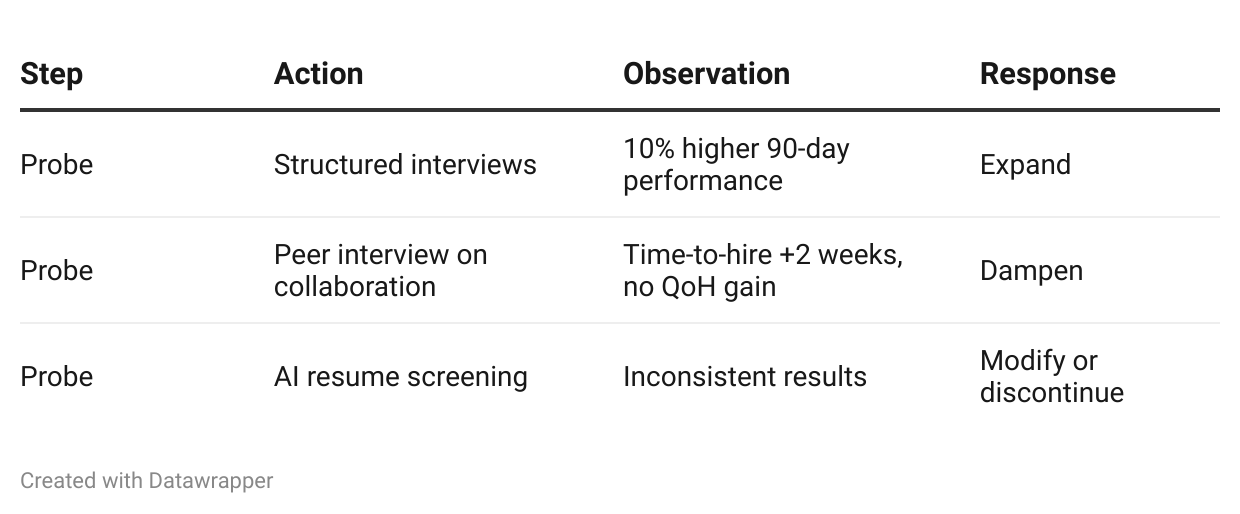

Step 1: Probe — Run Safe-to-Fail Experiments

Recruiters conduct small, controlled experiments to explore what might improve QoH:

These pilots are safe-to-fail — small-scale, reversible, and informative.

Step 2: Sense — Monitor Emerging Patterns

Recruiters collect leading indicators and qualitative insights:

Quantitative: Early attrition, 90-day performance, hiring manager satisfaction

Qualitative: Candidate experience, peer feedback, onboarding feedback

Then, patterns may emerge:

Structured interviews → higher early performance

Potential assessments → improved cultural alignment but longer time-to-hire

Recruiters interpret patterns that emerge, not just isolated metrics.

Step 3: Respond — Amplify or Dampen

Actions based on sensed outcomes:

Amplify effective interventions (e.g., expand structured interviews)

Modify mixed results (e.g., refine assessment tools)

Dampen ineffective probes (e.g., retire low-impact steps)

This iterative loop evolves a context-specific QoH strategy.

Example: Engineering Hiring QoH Initiative

Emergent best practice: Structured interviews + calibration sessions yield best QoH outcomes.

The Path Forward

The recruitment industry’s struggle with quality of hire isn’t a failure of measurement sophistication. It is the error of applying complicated problem solving to a complex issue.

The solution isn’t better formulas or more sophisticated analytics. It’s adopting measurement philosophies that are appropriate to the complexity.

This requires humility about what can be known in advance and confidence in our ability to sense and respond to emerging patterns. It means accepting that hiring will never be perfectly predictable while still maintaining that it can be systematically improved through intelligent experimentation and pattern recognition. Most fundamentally, it requires recognizing that when we place humans into social systems, we’re working in the domain of complexity, where the rules are different. Our measurement approaches must also be different.

Quality of hire can be measured in ways that are timely and useful, but only if we stop pretending it’s a complicated problem waiting for the right formula and start treating it as the complex adaptive challenge it actually is.